Wes Streeting has developed a reputation for running his mouth off, whether accusing Jeremy Corbyn of being senile or dissing the NHS. But instead of deriding his tendency to pick unnecessary fights, it's worth attending to the language he employs, if only because he is one of the few shadow frontbenchers whose rhetoric rises above the mundane, even if only to reach the giddy heights of invective. This week he has taken to Twitter to berate those on the left who have criticised him for mistaking the willingness of confirmed Conservative voters to switch to Labour as the product of those voters' movement leftwards rather than the party's move to the right. His defence ignores the rationale of the voters entirely and opts instead for the usual left-bashing, but his choice of words is more interesting than that might suggest: "I'm from a centre-left tradition that seeks converts, not traitors. That's how we win elections and change the lives of people who don't have the luxury of settling for self-gratifying ideological purity under a Tory government."

In a retweet, James Meadway ignored the insults and focused on the mathematics: "I'm not from a centre-left tradition but w/out winning over Tories, we don't win. Not just about winning elections - it matters for winning strike ballots & workplace organising, for organising protests, for anything. Shouldn't be left to Wes Streeting et al to claim the argument." It's trivially true that you win a general election from opposition by attracting people who voted for the governing party in the previous ballot, but it's also true that much of the heavy lifting is actually done by demoralising your opponent's supporters and thus depressing their vote. New Labour was a famous case in point as they oversaw a fall in general election turnout in both 1997 and 2001 (the second, at 59%, marking a 19-point fall since the 78% turnout of 1992). Every general election in the post-2008 era has been determined by the parties relative success in getting out their vote (as was also the case with the EU referendum). The next election will almost certainly be decided by the Conservative's ability to motivate and re-energise their supporters.

James's pragmatic focus on "winning over" reflects the traditional election model in which a decisive subset of the electorate can be swayed by convincing campaign offers - the premise being that voters select parties on the basis of which might best meet their short-term interests. But not only does this provide a poor model for understanding general elections since 2010, it also elides the more interesting idea that crouches behind Streeting's use of the term "converts". That suggests something beyond the merely instrumental: the scales falling from voters' eyes, a revelatory light from heaven on the road to Damascus. But does that reflect how the Labour Party has historically built a winning electoral coalition? You might make the case for 1945's "New Jerusalem", but the conversion to social democracy was clearly a product of wartime and a determination not to return to the political economy of the 1930s. In other words, it followed a shift in society that Labour reflected rather than inspired. The radical manifesto was popular before it was persuasive.

There are two parts to Streeting's claim. The less interesting is the strawman of a self-indulgent left, divorced from the real concerns of the electorate and contemptuous of the need to win. The interesting part is the idea that he comes from an identifiable tradition that actively seeks converts. But where is that tradition to be found? It certainly isn't on the centre-left of Labour - a space that few people would think Streeting occupies anyway - not least because that isn't a consistent intellectual tradition within the party so much as a demilitarised zone between the left and right. The received wisdom in the aftermath of the 2019 defeat - Corbyn was repellent on the "Labour doorstep" and the manifesto contained too many promises - highlighted the Labour right's historic aversion to zealotry and its policy conservatism, but what it didn't do is suggest that it had an alternative programme likely to attract anything as positive as "converts". At best, it's implicit offer was to avoid alienating "traditional Labour voters", and to do so by promising minimal change. This owed more to Anglicanism than Methodism, let alone Marxism.

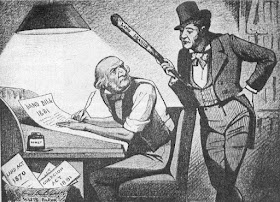

In the real world, conversion is rare. Inertia, as much as the stubbornness of belief, means that few people change either their politics or their religion (assuming they have either); and those that do so tend to be strong believers, not weak ones - hence the zeal of the convert. Politicians fully understand this, and they also appreciate what to them seems like the inescapable conclusion: that their message should be geared to attracting the shallow and lukewarm (the "floating voter"). This militates against any idea of evangelical fervour, let alone conversion. The result is performativity (patriotism, caution), vapidity (aspiration, innovation), and a refusal to get bogged down in policy detail beyond the emblematic ("We won't re-nationalise water"). So what is Streeting up to when he employs the word "converts"? Is it simply a hyperbolic antonym that allows him to justify "traitors" and so accuse the left of paranoid group-think? Or does he genuinely believe he represents a distinctive programme that is both persuasive and in tune with the times? Even Keir Starmer's fans in the media fret that the party lacks distinctive policies or a big idea, and nothing Streeting himself has proposed marks an advance on the New Labour years. His contribution has been rhetorical trenchancy, not original thought.

In the history of organised British politics, genuine conversion (as opposed to careerist opportunism) has tended to flow from the centre to the left (i.e. radicalisation in the face of experience), with conversion in the other direction often bypassing the centre and heading straight to the right (e.g. Trotskyists becoming Neo-conservatives or the trajectory of the RCP). The Labour Right was long wary of zealotry and thus conversion because it was the implacable enemy of the left, but that changed with the neoliberal entryism of the late-80s and early-90s. At that point there was a conscious attempt to develop an orthodoxy (something to convert to that was more substantial than Labourism) based on the "third-way" and "radical centre" popularised by Anthony Giddens. One consequence of this has been a greater commitment to ideological purity, which in turn has led to an even more intolerant attitude towards the left and an unwillingness to compromise (there is no longer any pretence of a "broad church"). Streeting's comment about the left "settling for self-gratifying ideological purity under a Tory government" is obvious projection given the attempted sabotage of Labour's electoral chances in 2017 and 2019.

But while the New Labour years certainly birthed a comprehensive orthodoxy that spanned social policy as well as economics and the management of the public sector, this did not lead to any mass conversion among the wider electorate, comparable say to the cultural revolution of the early-1940s. The testaments of enlightenment and the acknowledgment of prior error were limited to members of the commentariat, as they busily readjusted their beliefs to suit the new regime. The most obvious evidence of Labour's lack of interest in any broader conversion was the declining membership of the party itself. While that was arrested and reversed during the Corbyn interlude, it is clear that normal service has since been resumed. Not only is the current leadership more interested in attracting old donors than recruiting new members but it is actively seeking to expel anyone who might be considered zealous. Proscribing groups and marking members down for liking tweets by Green MPs isn't about ideological conformity so much as a determination to winnow out anyone who joined the party because they held strong political opinions.

One of the defenders of Streeting on Twitter claimed that George Orwell was the author of the line: "The right seek converts, the left looks for traitors." Of course, he said nothing of the sort. The maxim originated with the American journalist Michael Kinsley and its original form was: "Conservatives are always looking for converts, whereas liberals are always looking for heretics". This doesn't even make sense in the context of US politics: conservatives cultivate their opponents as hate figures and would be at a loss if they were to convert en masse, while liberals are more likely to stop inviting you to their dinner parties than to burn you at the stake. And it is perhaps because it doesn't make sense that the line has been so easily taken up by British centrists who imagine it condemns both the right for its evangelical zeal and the left for its paranoid totalitarianism. But Streeting has changed the meaning to suggest that being a political evangelist is actually a good thing. Why would he say that?

Streeting's talent, for which he is hailed as a future leader, is emotional language, whether talking about his backstory or his determination to be the "patients' champion". His invention of a "centre-left tradition" of proselytisation could be categorised simply as hyperbole, but I think it also points to something else. There is an "inner party" in British politics that spans more than the PLP and extends to much of the supporting cast of the media (this is not a conspiracy - it's simply the establishment). Streeting's emotionalism gives us an insight into the inner party's thinking. They are not seeking to convert Tory voters into Labour supporters - the electorate are just ballot fodder to them - but there is a mission underway to convert the remaining spaces of resistance within the media, particularly those that arose in the wake of 2008, to the programme of the inner party, and that programme is the re-establishment of the neoliberal state after the neglect of the Tories and the unexpected threat posed by Corbyn.

It has long been fashionable to accuse the left of stubbornly pursuing its venerable dogma in the face of the repeated rejections of the electorate and (after 1989) the judgement of history. This not only ignores the history of left thought, which has always been more various and mutable than its critics allow, it also distracts from the way in which the judgement not only of history but the earth itself (i.e. climate change) has rejected neoliberalism. Despite this, the Labour party under its current leadership seems incapable of offering anything beyond a resurrection of the decade after 1997. While the public presentation of politics emphasises the pragmatic and eschews ideology, that inner party remains wedded to neoliberal orthodoxy and vigilant against ideological heretics. This is not the evangelical mass-movement that Streeting's choice of words might imply but an elitist sect at the heart of the British establishment.